Here is the first of three posts on the story we know as The Parable of the Prodigal Son found in Luke 15:11-32. The story Jesus tells of a father and his two sons has been a favorite of many people and for good reason. But the story is more than just a prodigal child and when we pay attention to the story, perhaps we’ll discover that Jesus is telling us about the prodigal gospel he is proclaiming.1

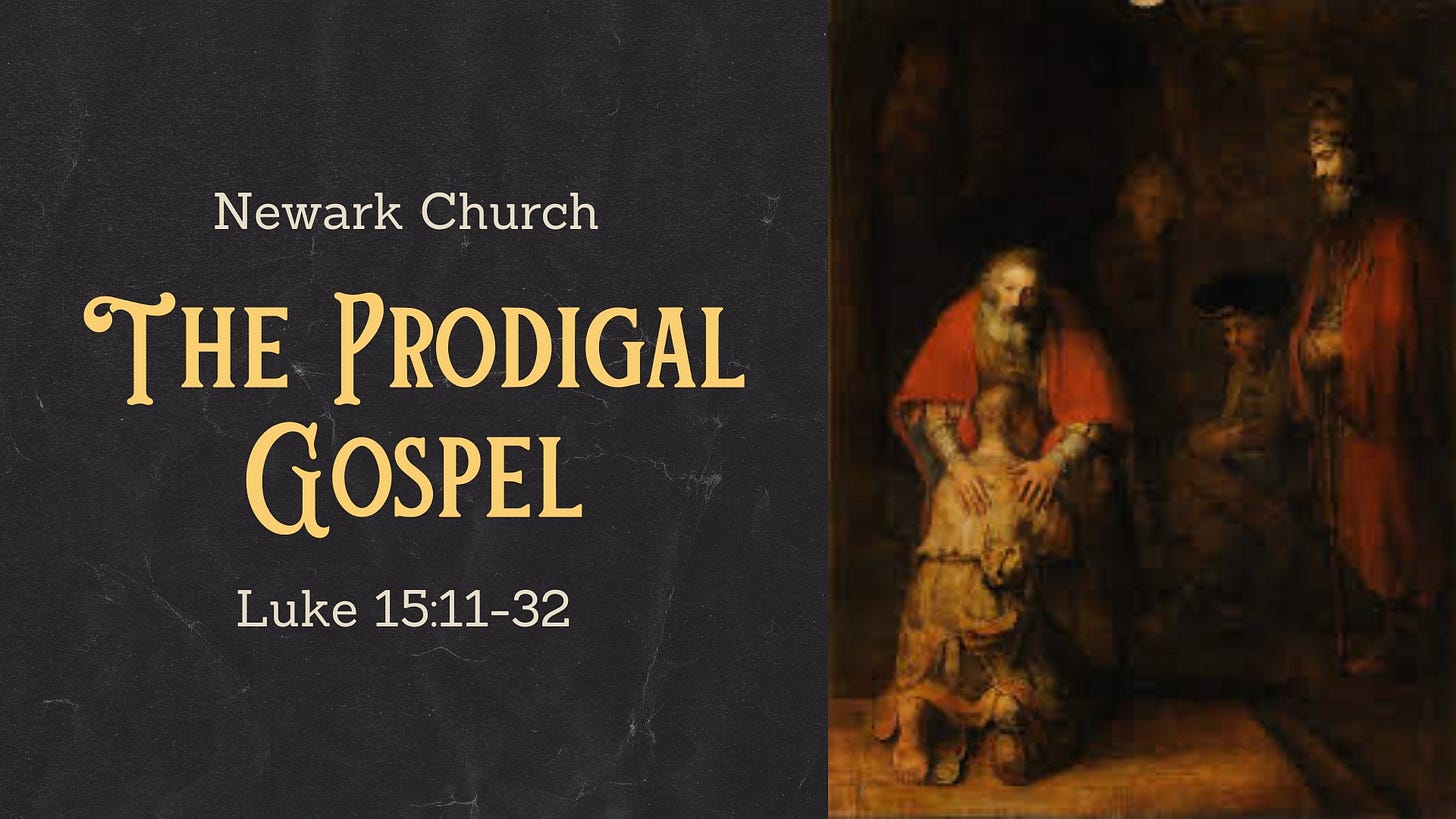

The picture above includes Rembrandt’s painting The Return of the Prodigal Son. I don’t know if you can see it clearly but in Rembrandt’s painting, you have the father embracing his younger son with the older son looking at them. But behind the father and his two sons are two other people, who are just bystanders. Have you ever thought about who the bystanders are? Or perhaps wonder about who the bystanders are today? These questions are something to let simmer as we read the text from Luke 15:11-32

Jesus continued: “There was a man who had two sons. The younger one said to his father, ‘Father, give me my share of the estate.’ So he divided his property between them. Not long after that, the younger son got together all he had, set off for a distant country and there squandered his wealth in wild living. After he had spent everything, there was a severe famine in that whole country, and he began to be in need. So he went and hired himself out to a citizen of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed pigs. He longed to fill his stomach with the pods that the pigs were eating, but no one gave him anything. When he came to his senses, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have food to spare, and here I am starving to death! I will set out and go back to my father and say to him: Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired servants.’ So he got up and went to his father. But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms around him and kissed him. The son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ But the father said to his servants, ‘Quick! Bring the best robe and put it on him. Put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. Bring the fattened calf and kill it. Let’s have a feast and celebrate. For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’ So they began to celebrate. Meanwhile, the older son was in the field. When he came near the house, he heard music and dancing. So he called one of the servants and asked him what was going on. ‘Your brother has come,’ he replied, ‘and your father has killed the fattened calf because he has him back safe and sound.’ The older brother became angry and refused to go in. So his father went out and pleaded with him. But he answered his father, ‘Look! All these years I’ve been slaving for you and never disobeyed your orders. Yet you never gave me even a young goat so I could celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours who has squandered your property with prostitutes comes home, you kill the fattened calf for him!’ ‘My son,’ the father said, ‘you are always with me, and everything I have is yours. But we had to celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’”2

As I mentioned above, most people familiar with this story in Luke 15 know it as The Parable of the Prodigal Son. With such a label as The Parable of the Prodigal Son, which isn’t actually in scripture, the focus is placed on the younger son as the lost son. Yet the story Jesus tells involves a father and his two sons. Each son has his own set of problems and with each son, the father responds in a manner that reveals the true heart of the father. In fact, the father shows himself to be the real prodigal in this story. What’s more important is that as Jesus tells this story, we might just discover that the true prodigal is God revealing to us a prodigal gospel.

I know the word prodigal isn’t that common today but when we do hear the word used, a negative connotation probably comes to mind. After all, describing the younger son as “the prodigal son” certainly isn’t a compliment. We think of him as a prodigal because he acts in a prodigal manner, recklessly burning through his inheritance as he makes foolish choices. As Jesus tells the story, our text says, the younger son took his father’s wealth and “set off for a distant country and squandered his wealth in wild living.”

Foolishness. Terrible life choices and outlandish behavior. It ain’t good. But according to the Random House College Dictionary that sits within arms reach in my office, the word prodigal means “giving or yielding profusely; lavishly abundant.”3 So when we encounter someone with extraordinary talent as a musician, we have a prodigy and when there is a torrential downpour, we end up with a prodigious amount of rainfall. The word prodigal simply describes the act of giving something lavishly or generously.

So Jesus tells us a story about a father and two sons. We’re told first about the younger of the two sons, who comes to his father asking for his share of the inheritance from his father’s estate. Quite bold, even by our cultural standards today. But in a traditional Middle Eastern context, such an ask is dishonorable.4 Sons are to remain serving their father but the son wants his inheritance so that he can take off on his own and make his own way.

But the father, who loves his son just as any father should, grants his son’s request. Dad’s not going to stop his son from walking out the door. As much as it must pain the father, true love is never coercive. Sometimes love hurts because it means loving someone who spurns that love. In this case, love means the father will give his son the freedom given to away even though the father knows things are about to go bad. So the son gets his way. He gets his inheritance and leaves, only to discover that life on his own is really difficult. Imagine that. Life’s especially difficult when passion rules the game and that’s putting it nicely.

In the story Jesus tells, the younger son lives through both natural evil and moral evil—the two categories philosophers and theologians use to speak of the wrongs in the world. Like hurricanes and earthquakes, famine is a form of natural evil that brings a lot of suffering. Moral evil, on the other hand, involves sinful deeds that can yield suffering too. In the son’s case, the suffering of natural evil is made even worse by his own moral evil.

Staying out at all hours of the night, partying, and hopping from one club to another sure seems like fun. Or at least that’s how it’s always portrayed… But eventually, the party dues come due and sometimes those dues are quite expensive. Away from the care of his loving father, the dues come and they’re quite expensive. So expensive, the son can’t pay. Realizing the game is over and he’s on the losing end, the young son sets out for his father’s house. Perhaps he can come home if he offers himself to be just one of his father’s hired servants. “But,” as the story says, “while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms around him and kissed him.”

What a surprise! No rebuke and no shame, just compassion to go along with a hug and kiss. That’s called love and given the circumstance, it’s a lavish love. The father could have refused his son and turned his back on him but the father was looking for his son because he loves his son. Nothing the son has done has changed how much the father loves his son. So the father now becomes the prodigal, expressing the love he has for his son in a lavish manner.

And Jesus… Church, let me tell you about Jesus. At the beginning of Luke 15, we are told that Jesus is having dinner with the sinners and tax collectors, while the Pharisees and scribes grumble because Jesus is eating with such people. So what does Jesus do?

Well, Jesus tells a parable. Not just one, and not two but three parables.5 The first one is about a lost sheep and the second is about a lost coin. In both parables, when the lost sheep and the lost coin are found, there’s rejoicing. And then Jesus tells a third parable about a father and his two sons. Two sons who both have their problems but two sons who are loved by their father and nothing has ever changed that. In the context of Luke’s Gospel, Jesus is really telling a story about God and his children, both Israel and the Gentiles. Or shall we say, both the sinners and the religious do-gooders? And that means the story Jesus is telling is about God’s love for us too.

Every one of us, no matter what we’ve done or where we’re at with God, we are loved by God. In the parable, the father can see his son from a far-off distance because he’s out looking for his son like any loving parent would do if their child was lost. But in real life, we’re the ones who are lost or at least were lost at one time. Whether that is lost in the sin of foolish choices and wild living like the younger brother or lost in the sin of self-righteousness and entitlement like the older brother, lost is still lost.

The good news and what makes the story of Jesus Christ and the kingdom of God a prodigal gospel, is that God has never stopped loving us. No matter where we are and what we’ve done, God has continued to love us with more love than we can imagine. God’s love for us is so generous and prodigious that he’s filled with compassion for us—to suffer with us—in the person of Jesus to find us. In fact, the love of God is so generous and prodigious that God’s Son, Jesus Christ, dies for us so that we don’t have to remain lost anymore.

Jesus is telling us this story of a father and his two sons as an illustration of God’s love. As Henri Nouwen wrote in his book The Return of the Prodigal Son, “The story of the prodigal son is the story of a God who goes searching for me and who doesn’t rest until he has found me. He urges and he pleads. He begs me to stop clinging to the powers of death and to let myself be embraced by arms that will carry me to the place where I will find the life I most desire.”6

So let’s talk about life. Every one of us are sinners. Fortunately, we’re not here to catalog everyone’s sin. But sinners we are. Maybe we haven’t made a huge mess out of our life like the younger brother and maybe we’re not so smug in our religiosity like the older brother. But like the two bystanders in Rembrandt’s painting, we’re leaning in and listening because we know that we’re no better than either brother.

But life is life and sometimes life is difficult too and sometimes hearing talk about the love of God and knowing the love of God are two different matters. And let me remind us that our enemy, Satan, is always lurking and trying to tell us that we’re bad people… that there no good in us, that God hates us because we’re sinners. That’s a bunch of nonsense and that’s putting it nicely. It’s nonsense because the story Jesus is telling is about God’s love for us, a love that is expressed in abundance—a prodigal love.

Years and years ago, all the way back in 1979, singer and actress Bette Midler sang a song called The Rose. It’s a love song. Some might even say a sappy love song but it was a number-one hit and from a poetic standpoint, the lyrics are a work of art. Here are the lyrics from the third verse:

When the night has been too lonely and the road has been too long, and you think that love is only for the lucky and the strong. Just remember in the winter, far beneath the bitter snow, lies the seed that with the sun's love, in the spring becomes the rose.7

Well, someone might need to hear this: God’s love is the seed, and the Son’s love, the love that Jesus Christ gives in the shedding of his blood on the cross, is your hope. And spring is upon us. We might feel completely lost but this prodigal love of God is your promise of hope. Yes, like the conversations the father has with his two sons, God may need to do some soul work with us through the power of the Holy Spirit. But the redemptive formation in Christ is more than possible because God loves us more than we can ever imagine.

If you hear me say nothing else, I hope you’ll hear me reminding you that God loves you because sometimes in life it is only the love of God that sustains us. And for those of you who are younger, who have yet to leave your parent’s house… You’ve got your whole life ahead of you but along the way, you just might make some poor choices as we all do. Some of your choices may take you down a difficult path. But I hope you’ll remember that you are loved by God because knowing that God loves you will help you to see the arms of God reaching out in love in your darkest moments. As the apostle Paul wrote, “For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 8:38-39).

The story Jesus tells of a father and his two sons isn’t just a story about a prodigal son, it’s the story about a prodigal God revealing his prodigal love to us in Jesus Christ. That’s why Jesus is fellowshipping with sinners because no matter what our sins are, the love of God is for us and seeks to find us so that we may be lost no more.

With a few slight alterations, this post was originally the manuscript for a sermon titled Prodigal Love that I preached to the Newark Church of Christ on Sunday, June 9, 2024.

Unless otherwise noted, all scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Jess Stein, ed., The Random House College Dictionary, rev. ed. (New York: Random House, 1988), 1056.

C. F. Evans, Saint Luke, TPI New Testament Commentaries (Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1990), 592.

Brendan Byrne, The Hospitality of God: A Reading of Luke’s Gospel, rev. ed., Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2015, 147, the parable joins with the previous two parables of the lost sheep and lost coin to ask those who would exclude others from the kingdom if they can accept that God loves and welcomes all people, including the sinners, into his kingdom.

Henri J.M. Nouwen, The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming (New York: Doubleday, 1992; reprint, New York: Image Book, 1994), 82.

Amanda McBroom, “The Rose,” recorded by Bette Midler, Atlantic Records, 1979.